A hero from the shoreline

the sea worm that solved a decades-long puzzle

For decades, researchers tried to develop safe and effective hemoglobin‑based oxygen carriers (HBOCs). Early approaches often modified bovine hemoglobin or expired human hemoglobin. Many projects ultimately failed because of severe side effects — especially vasoconstriction (blood‑vessel tightening), which can raise blood pressure and harm tissues.¹

Surprisingly, a key answer came from nature: a lugworm living on the coast of Brittany, France (Arenicola marina).

On an ordinary-looking beach, the answer medicine has been searching for over decades may be hiding in plain sight

Life in the intertidal zone: evolution’s extreme training ground

Lugworms live buried in sand in the intertidal zone — a harsh habitat that switches between two extremes each day:

- High tide: oxygen‑rich seawater arrives.

- Low tide: oxygen can drop sharply in the sand (hypoxia).

To survive, lugworms evolved an extraordinary oxygen‑carrying system. Their hemoglobin circulates outside cells (extracellular hemoglobin), helping them store and deliver oxygen even in low‑oxygen conditions.²

A life cycle that swings between oxygen-rich and extremely low-oxygen conditions is nature’s ultimate stress test.

Dr. Franck Zal’s World-Changing Question

In 2007, Dr. Franck Zal, a marine biologist and the founder of Hemarina, looked at the lugworm from a completely different perspective. With more than 15 years of experience studying organisms in extreme environments, he asked a simple but powerful question:

“How can this living organism survive such severe oxygen deprivation?”³

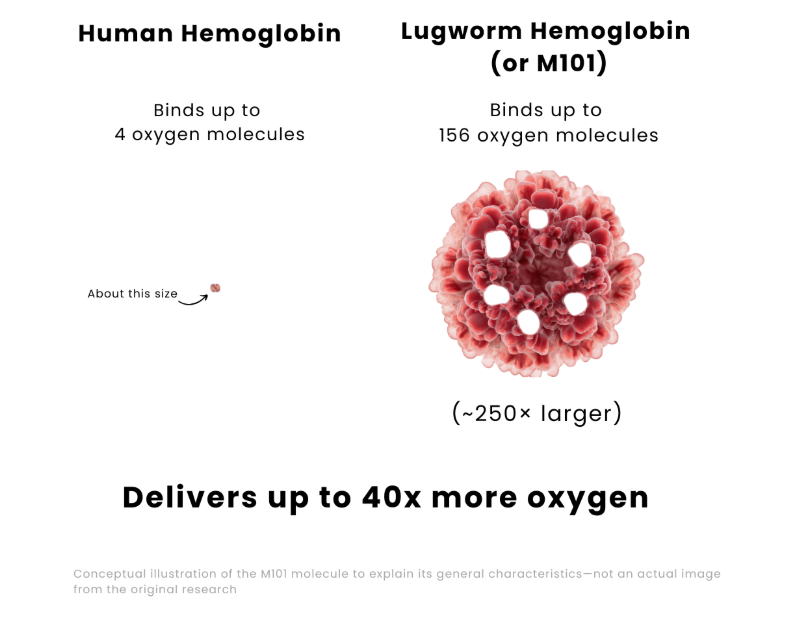

That question led to a landmark discovery in the lugworm’s blood. Unlike human hemoglobin, which is packed inside red blood cells, the lugworm’s hemoglobin circulates freely in the bloodstream. Even more remarkably, it shows advantages over human hemoglobin in multiple ways:

- Giant molecular size: about 250 times larger than human hemoglobin.

- Oxygen-carrying capacity: can transport about 40 times more oxygen than human hemoglobin, because one molecule can bind up to 156 oxygen molecules.⁴

- Universal compatibility: because it is an extracellular hemoglobin, it has no blood group antigens, meaning it can potentially be used in any patient without blood typing.⁵

The lugworm’s giant hemoglobin molecules (right) can carry up to 40× more oxygen than human hemoglobin (left)

Source : Batool, F et al. Therapeutic Potential of Hemoglobin Derived from the Marine Worm Arenicola marina (M101): A Literature Review of a Breakthrough Innovation. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 376

Why this matters for medicine

One major reason earlier HBOCs failed is that free hemoglobin can interfere with nitric oxide (NO), a molecule that helps keep blood vessels relaxed. When NO is depleted, vessels constrict and blood pressure rises. The lugworm’s extracellular hemoglobin is structured in ways that reduce this problem, making it a promising blueprint for safer oxygen carriers²

This natural “design solution” became the foundation for the molecule later known as M101.

Work cited

-

Alayash, A. I. (2004). Oxygen therapeutics: pursuit of protein-based blood substitutes. Clinical Chemistry, 50(9), 1546-1554. อ้างถึงใน A bloodless revolution. EMBO reports, 6(8), 719–722.

-

Rousselot, M., et al. (2006). Arenicola marina extracellular hemoglobin: a new promising blood substitute. Biotechnology Journal, 1(3), 333-345.

-

Hemarina. (n.d.). A human, scientific, and entrepreneurial adventure. Retrieved from hemarina.com

-

Batool, H., et al. (2021). Therapeutic Potential of Hemoglobin Derived from the Marine Worm Arenicola marina (M101): A Literature Review of a Breakthrough Innovation. Marine Drugs, 19(7), 376.

-

Atlanpole Biotherapies. (2021, November 12). World first: a double forearm transplant thanks to marina lugworms from the company Hemarina.